Architect-Friendly, Child-Tolerant

By CONSTANCE ROSENBLUM

Published: October 16, 2009

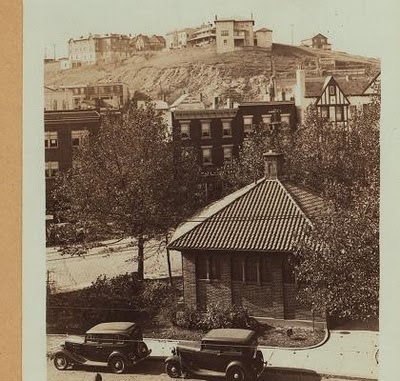

ON Fort Hill Circle in St. George, Staten Island, nestled amid an assortment of shingle style, Italian Renaissance, Dutch colonial and Tudor houses, there sits an unassuming red-brick split-level. This structure was designed by a local architect named Albert Melnicker and built in 1949 by the Lipsons, a dentist and his wife.

Tina Vultaggio, 39, an architect who grew up in the island community of Great Kills, and her husband, Kevin Rice, 40, an architect from Houston, met the Lipsons nearly a decade ago.

Mr. Rice and Ms. Vultaggio were newly married and had been stunned by the price tags they saw when they went house hunting in Brooklyn and Manhattan. But when they met the Lipsons, who at that point were in their 80s and already spending much of the year in Florida, things began looking up. The possibility of acquiring the older couple’s house on Fort Hill Circle, which was priced at $325,000 and had 1,900 square feet of space, was immensely appealing.

By Sept. 11, 2001, they were in contract, with the closing set for three weeks later. The morning of the terrorist attacks, the younger couple, who at the time both worked in Manhattan, emerged from the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel minutes after the plane hit the first tower and watched, horrified, as scraps of paper from the offices flew through the air.

It seemed the worst possible moment to be buying a piece of the city.

“We asked ourselves, should we be buying in New York at all?” Ms. Vultaggio recalled.

Her husband added: “We wondered, should we walk away from the deposit? Should we move to Montana?”

Despite misgivings, they decided to proceed. And now, eight years later, they are well settled in the trim brick house. The household now includes a son, Jonathan, 3. And they have no regrets.

Throughout the house are items appropriate to a couple who both have careers in the world of design. Mr. Rice is the project leader for the redesign of Lincoln Center’s public spaces at Diller Scofidio & Renfro, a firm whose work includes the redesign of the High Line. Ms. Vultaggio works as an urban designer in the Staten Island office of New York’s Department of City Planning.

Unsurprisingly, both are what Mr. Rice describes as “unrepentant Modernists.”

“There’s something very appealing about this midcentury period,” he said of the house. “The open layout, the way everything flows. There’s lots of light.”

Being architects, they talk a lot about the elevation of the house, the face it presents to the world. They are taken with the fact that the windows are modular casement units all the same width, combined in a variety of arrangements.

Yet as much as the couple love the bones of the house, over the years they have made changes. The first thing they did after they arrived was rip out the living room’s white wall-to-wall carpet, which covered a pristine oak floor. Next up came the small windows in the dining area, then sheathed by white curtains and painted shut. The windows are now exposed and flood the space with light.

The living room is furnished largely in white — “We’ll re-cover the sofa when he’s 6,” Ms. Vultaggio said gesturing toward her son, who this day was banging away at Tinkertoys in a corner — and the furnishings are pleasantly eclectic. A Corbusier chaise longue — “Nearly every architect has one,” Mr. Rice said — sits opposite a turn-of-the-century oak breakfront from Texas.

On a wall in the entryway are spare 18th-century prints from a treatise on architectural education by Bernardo Vittone, an Italian architect from the Rococo period. Here and there are pieces of furniture that Ms. Vultaggio describes as “fancy Italian things that were bought at sample sales but that we couldn’t have afforded otherwise.”

When you walk into the kitchen, you feel as if you have entered a hall of mirrors, so gleaming are all the surfaces. The countertops are covered with gray-green Swiss gneiss, the shelves are a rich cherry wood, the glass tiles on the walls glow with a cool greenish tint, and all the appliances are stainless steel.

The design of what was originally a galley kitchen, which the couple redid largely by themselves, looks as if the space could have been reconfigured no other way. But even for a pair of architects, inspiration came slowly.

“We started drawing designs when we first moved in,” Mr. Rice said. “We were sketching it for three years.”

For better and sometimes worse, the house came equipped with many of the original furnishings. Some have been lovingly preserved, and others were retrofitted for a new century, as is especially evident in the family room. The table and chairs are Danish modern, and the sofas are the work of a Modernist designer named Harvey Probber, who enjoyed a brief flurry of late-in-life attention in trendy venues like Wallpaper magazine. (If you turn over the turquoise cushions, you can see the original nubby orange fabric.)

The macramé blinds are original, as is the pecan paneling, which Mr. Rice describes as “real wood veneer.”

“Very Brady Bunch,” his wife said dryly.

Period touches also abound upstairs, among them the original square tub in one of the bathrooms, a cast-iron fixture configured on the diagonal and executed in a color Ms. Vultaggio likes to call pistachio. The sailboat mobile in Jonathan’s bedroom is a decorative accent appropriate for a child whose mother’s résumé lists her main interest as “sailing on Raritan Bay.”

In the back of the house is a patio, which Mr. Rice built with his father-in-law one Saturday afternoon. It is equipped with not one but two grills — one gas, one charcoal — because, as Mr. Rice pointed out, “I’m from Texas, and I’m not letting go of my culture.”

The patio faces an expanse of lawn fringed with greenery, including what Mr. Rice describes as “the obligatory fig tree,” a cherry tree acquired through the city’s MillionTreesNYC program, and arugula grown from seed provided by Ms. Vultaggio’s father. In this tranquil space you can hear the bells from Brighton Heights Reformed Church and watch the antics of the resident squirrels, cardinals and blue jays.

Ms. Vultaggio’s mother, who comes by twice a week to baby-sit, still lives in the house her daughter knew as a child. But even though Ms. Vultaggio has returned to the island of her birth, she does not feel as if she were shuttling back in time.

“I felt this was different from the Staten Island I grew up in,” said Ms. Vultaggio, who is a first-generation American. (Her parents came from Italy.) “It’s more urban and diverse, and a lot of the people who live here came from someplace else. When I moved back, I didn’t feel as if I was coming home.”